The Joseph Skakun Project

ABOUT US

The Joseph Skakun Project is a 501 (c) (3) federal tax exempt charity, founded by Michael Skakun, an author and son of genocide survivors, to educate future generations about the enormity of the Holocaust, as well to convey the power of the resilient imagination in surmounting extremity. This cultural and memory initiative will convey the message of human solidarity and tolerance via innovative programs in the realms of education, the performing arts and interfaith dialogue.

Founder: Michael Skakun MBA FRSA

Michael Skakun, born in Jaffa, Israel, and raised in New York, has served as a journalist, author, and translator. As a public affairs specialist, he has worked for National UJA and Israel Bonds, and the Congress for Jewish Culture, as well as a host of non-profit organizations and Jewish institutions where he’s cultivated a wide network of contacts and associations. He has served at such publications as the Forward (both English and Yiddish), the Litchfield County Times and the New York Observer as cultural writer and book reviewer.

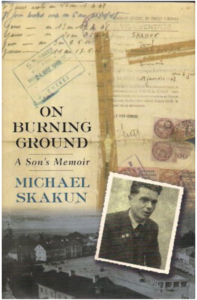

The son of Holocaust survivors, he is the author of “On Burning Ground: A Son’s Memoir” (St. Martin’s Press), the story of his father’s nerve-peeling, inspirational wartime survival. The recipient of a starred and lead review in Publisher’s Weekly, the book was described as “distinguished by outstanding writing and moral complexity.” The Washington Post labeled this tale of extreme masquerade the “The Story of a Holocaust Houdini.” In the “Oprah” reissue of his classic “Night,” Noble Peace Prize winner Elie Wiesel chose “On Burning Ground” as one of five books for advanced reading about the Holocaust, in the company of “The Pianist” and “The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich” among others. A feature film based on this story is now in preparation. Michael was elected a fellow of Royal Society of the Arts in 2022.

On Burning ground: A Son’s Memoir

by Michael Skakun (St. Martin’s Press)

“On Burning Ground” traces how at the height of World War II, Joseph Skakun, a devout blond-haired European rabbinical student steeped in a legendary form of ethical piety, as well as trained in the analytic rigors of talmudism, adopted multiple religious and ethnic identities, including those of a Christian and a Muslim, to survive. The story culminates with his desperate gambit at life – his entry as a volunteer recruit into Hitler’s Waffen-SS, the most feared and fearsome of Hitler’s fighting divisions.

The Washington Post went on to say: “To assume a fake identity is not so strange; spies and lesser impostors do it all the time. But for a devout yeshiva student to invent a combination of false selves through which he not only escapes the Nazi death camps but actually ends up as a recruit for the Waffen-SS – now there’s a definition of chutzpah (nerve).” After the war, the wheel comes full circle as Joseph Skakun, in a post-traumatic fog of anguish and doubt, manages to return to his ancestral faith first in Paris and then in New York.

Vivre et c’est tout (On Burning Ground)

Michael Skakun

Préface de Marek Halter

Robert Laffont

Traduit de l’anglais (américain) par Viviane Mikhalkov

« Quelle vie ! Cette histoire, il fallait la raconter » Elie Wiesel

Avec beaucoup de pudeur, Michael Skakun nous raconte l’incroyable histoire de son père, qui a hanté toute son enfance… : comment, à Novogrudek, en décembre 1941, Joseph, jeune étudiant qui se destine au rabbinat, sauve sa mère d’une rafle nazie ; comment, après sa disparition (elle n’échappera pas à une seconde rafle), Joseph décide de fuir, seul, son village et les siens ; comment sa blondeur lui donne l’idée d’adopter une identité chrétienne ; comment il se fait envoyer comme travailleur volontaire près de Berlin, au cœur du Reich ; et comment le piège se referme sur lui et le contraint de s’enfoncer toujours plus loin dans l’impensable pour sauver sa peau : devenir SS, en se faisant passer pour un citoyen lituanien d’origine musulmane.

C’est dans la gueule du loup que Joseph est allé chercher la plus sûre des protections. Heureusement, la guerre finit avant qu’il n’ait à commettre l’irréparable. Mais une question le hantera toujours : jusqu’où aurait-il été prêt à aller pour survivre ?

Vivre et c’est tout est un extraordinaire récit de survie en même temps que l’hommage d’un fils à son père et un livre d’une authentique qualité littéraire.

L’auteur : Michael Skakun est écrivain, traducteur et consultant auprès du Holocaust Memorial Council américain. Ce natif de Jaffa, en Israël, vit depuis toujours aux États-Unis.

Robert Laffont, Julliard, NiL, Seghers

24, avenue Marceau – 75008 Paris Téléphone : 01 53 67 14 0

THE RECEPTION OF "ON BURNING GROUND"

- In the Oprah Winfrey edition of his classic book “Night,” Nobel Prize laureate Elie Wiesel selected ON BURNING GROUND as one of five books for advanced reading about the Holocaust, in the company of “William Shirer’s “The Rise and Fall of Nazi Germany” and the Polish memoir, “The Pianist” (the basis of the film of the same name starring Adrian Brody).

- ON BURNING GROUND is headlined in The Washington Post as “The Story of a Holocaust Houdini.”

- ON BURNING GROUND receives a star and lead review in the industry trendsetter, Publisher’s Weekly.

- In a personal letter to the author, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger endorses ON BURNING GROUND, as do playwright Arthur Miller and British philanthropist Lord Jacob Rothschild.

- In a two-page spread entitled “The Jew Who Joined Hitler’s Infamous SS” the New York Post features the stranger-than-fiction survival story of Joseph Skakun, the protagonist of ON BURNING GROUND.

- “Stern,” Germany’s mass-circulation magazine, presents a five-page feature spread about Joseph Skakun, the subject of ON BURNING GROUND.

- C-SPAN repeatedly features the hour-long program of Michael Skakun discussing ON BURNING GROUND during “New York is Book Fair Country.”

- Author Michael Skakun is invited to the Harvard Faculty Club, in Cambridge, Mass., as well as the Columbia University Club in NYC, to discuss ON BURNING GROUND. Michael Skakun presents an evening devoted to ON BURNING GROUND at The National Arts Club in Manhattan.

- French edition of ON BURNING GROUND, entitled “Vivre et C’est Tout” (Edition Laffont, Paris) is prefaced by noted novelist/activist Marek Halter and appeared to excellent reviews in Le Figaro and other Parisian publications.

- ON BURNING GROUND has been published in:

- Japanese

- French

- Polish

- Romanian

- Language of the Crimean Tatars

- Belarusian

- German & Spanish (Awaited)

NAVARUDHAK (NAVAREDOK) – A Portrait in Miniature

by Michael Skakun

Cartographically speaking, Belarus lies at the very heart of Europe’s landmass. Polotsk, an important trading post on the River Dvina dating back to the Vikings, as well as a once golden spark of Jewish life, is smack at the epicenter of a continent, holding fast to its accolade, though villages in neighboring Lithuania insist that bragging rights are theirs.

Be that as it may, Belarus has, alas, been given short shrift by Western historians, dismissed as a historical afterthought, a mere geographical expression. Long regarded as an appendage of other nations, be it the Czarist empire or the Soviet Union, Belarus often got lost in the shuffle. Entire centuries appeared to hang suspended, unfixed to a master narrative, without which the various assemblages of fact and theory would not hold together. Across the Atlantic, assimilation did the rest. The descendants of Belarusian immigrants consigned the foreign-sounding names of their ancestors’ towns and villages to near oblivion, banished them to the back of beyond, a region betwixt and between, swallowed up by poverty, tedium and history and, all too often, by outright carnage. Indeed, this region has earned in our time the frightful sobriquet, “bloodlands,” a term brought up to date by the historian Timothy Snyder.

For Jews, however, historic Belarus, part of the realm of what was known as “Lita,” the land of the Litvaks, a region once governed by the Duchy of Lithuania (a region far larger than its latter-day namesake) never devolved into obscurity. This northern swath extending as far east as Smolensk, if not Muscovy itself, once part of the multitudinous Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a monarchy with an elected king and parliament dominated by local nobles, a forerunner of democracy, would come to play a signal cultural role in Eastern European Jewish history. How could it not when the Commonwealth encompassed virtually what is today Poland, Belarus and Ukraine, as well as most of the Baltic states. Indeed, “Lita” gave birth to a firm typology. The Litvak’s characteristics — a gift for learning and Talmudic exegesis, a taste for abstraction and in time for science, a special regard for the autonomy of perception and judgment, a flair for exposition, inquiry and skepticism, a wry, dry sense of humor – left an indelible stamp on the history of the Jews over time. Indeed, this characterization has stuck over the centuries, the very classic portrait of the “Mitnagdim“, the fierce opponents of the early rising tide of Hasidism, which spilled as far north as Lithuania and what is present-day Belarus. Viewing themselves as a powerful astringent against what they regarded as the excesses of ecstatic religiosity, the Misnagedim often sought to excommunicate these new celebrants of a febrile religion. However, the Lithuanian and Belarusian Hasidim never lost their Litvak pronunciation and psychological profile. Most especially, Chabad, the most internationally oriented of today’s Hasidic sects, widely acknowledged to be the gold standard in Jewish outreach, shows how ingrained Lithuanian-Belarusian traits prove to be. Chabad’s founder Rabbi Zalman of Liadi, in his masterpiece the “Tanya“, underscored the governing mind as the royal road to mystical union with the divine. Indeed, the very name of Chabad, which arose in what is today the easternmost parts of Belarus, is an acronym of the tri-partite structure of reason –“Khokhma, Bina and Da’at“. In this instance, as in many others, geography can be said to be destiny.

Photo credit: NN Teatr PL Shtetl Routes

Let us now narrow our searchlight and focus on a shtetl, at once singular and representative of what was best in Jewish Belarus. Nestled in the region’s northwest pocket, Navarudhak (Yiddish, Navaredok; in Belarusian, Russian and Polish it means “new township”), one of the oldest Belarusian towns founded in 1044 by Kievan princes, served as a trade route from Lithuania to Moscow in the late Middle Ages. Famous for its Jewish clergy and matzoh bakeries and infamous for its local seasonal fires, it evolved into a center of Jewish rabbinic leadership, as well as scholarship. Novaredok became home to towering talmudists such as Rabbi Yitzhak Elchonon Spektor, the foremost rabbinical authority in nineteenth century Russia, a wise and indefatigable leader, after whom the rabbinical seminary of New York’s Yeshiva University is named; as well as Rabbi Yechiel Michl Epstein, the spiritual leader of Navaredok for 34 years, a man who traced his family origins to the Spanish exile of 1492 and more antiquely to the banishment from Jerusalem two millennia ago by the Roman commander Titus. The author of the “Orakh Hashulkhan“, Rabbi Epstein’s magnum opus, a code of “halakha” (Jewish law), perhaps second only to that of Maimonides, placed him at or near the apex of Jewish learning. His rabbinic fame extended to his progeny: his grandson, Rabbi Meyer Berlin, the founder of Zionist Mizrachi Orthodox movement, which exercised great influence in inter-war Polish life and in the newly born State of Israel, and for whom the Israeli institution of higher learning, Bar-Ilan University in Ramat Gan, is named. Rabbi Yekhiel Michl Epstein of Navaredok went on to ordain some of the most prominent rabbis of his or any era: Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of British Mandatory Palestine, a formidable intellect and guiding spirit; Rabbi Yehezkel Abramsky, a head of the London Beth Din rabbinical court, whose son Chimen Abramsky, a left-wing intellectual and book collector supreme, hosted one of the most coveted cultural salons in the English capital; as well as Rabbi Yosef Shlomo Kahaneman, the head of the legendary Ponvezh yeshiva, a Zionist sympathizer, and the uncle of Professor Kahneman, the 2000 Nobel Prize winner in economics for his masterly work in the psychology of judgment and decision making. This pleiade of Jewish learning that drew its origin from Navaredok is as broad as the firmament itself.

Perhaps even more uniquely, Navaredok was the epicenter of the most ascetic variant of the “mussar” movement, moral instruction in right conduct, which exercised a fairly decisive influence on personal character development in Orthodox Jewish circles in Poland, Lithuania and Russia. An “echt Yiddish Tolstoyism,” it could be said to have brought rabbinic Judaism to the brink of monastic self-denial. The Vilna-born Chaim Grade, whom Elie Wiesel praised as “one of the great—if not the greatest–of living Yiddish novelists,” brilliantly examined and excruciatingly exposed in his classic novel, “The Yeshiva“, the dramatic philosophical and ethical dilemmas of those dwelling in the emotionally pinched yet ethically enlarging Novaredok mussar movement. Indeed, Navaredok, the cradle of the network of mussar yeshivas founded by Rabbi Yosef Yoyzl Hurwitz, an educational pioneer of the purest, as well as the austere, strain, proved to be a strong, if controversial, educational model for scores of yeshivas in pre-revolutionary Russia, including those in distant Kyiv, Kharkiv, Rostov-on-Dov, and Kherson, and later under the name of Bais Yosef, in independent Poland, taking up the instructional slack when other institutions could not.

Photo credit: Shtetl Routes Teatr NN.PL

Nowogrodek, as it was known during the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth period, as well as in the twenties and thirties of the last century, was a kind of literary Parnassus, a peak of Polish Romanticism. As the birthplace of Adam Mickiewicz, Poland’s literary bard, it assumed an important place in a budding national self-consciousness, all the more so as Poland lay under the jackboot of Czarist Russia. Mickiewicz, feted by Europe’s literati and cultural eminences–Chopin and George Sand in Paris, Pushkin in Moscow, Goethe in Weimar and Mazzini in Italy (the latter regarded him as the greatest poet of the age)–was the undisputed maestro of the Polish language, its felicities and flavors, as well as its poetic polyphony. A philosemite (his mother was regarded in some circle as a Frankist, a follower of the Jewish antinomian cult movement named after Jacob Frank, a false messiah), Mickiewicz was equally an Islamophile, whose “Sonnets of Crimea“, espoused a love of the region’s Muslim Tatars. He helped put Nowogrodek on the literary map of Poland with his magnum opus, “Pan Tadeusz” (Mr. Thaddeus), and eventually by sheer prophetic passion put literary Poland on the face of Europe as well.

Photo credit: Shtetl Routes NN Teatr.PL

Compromising a population of some 12,000 (of whom half were Jewish), interwar Nowogrodek was above all, a borderland town, looking out on the horizon of many cultures: Polish, Belarusian, Lithuanian, Jewish, Muslim. indeed, this ethnic amalgam gave rise to creative tension and ferment. During World War II, my father, Joseph Skakun, relied on the town’s multiple cultural valences to concoct a series of assumed new identities that allowed him to survive a war of annihilation. His is a tale of moral vertigo, a collision of worlds, the story an artful dodger who in a moment of greatest danger stitched together a “coat of many colors,” much like his biblical namesake, to outwit and outrun genocide. In “On Burning Ground: A Son’s Memoir” (St. Martin’s Press/Macmillan), I recount how he weaponized talmud and mussar to fashion a Christian/Muslim profile, allowing him to negotiate the most torturous twists and turns of a harsh and deadly destiny. Navaredok proved to be a cultural incubator permitting my father to craft a vehicle to by sleight of hand to confront the most terrifying ordeal of survival. See www.onburningground.com.

Navaredok’s defiant spirit also revealed itself at the height of the Holocaust in the illustrious bravery and supreme compassion of the Bielski brothers, who managed to save 1200 hundred Jews by escaping into the nearby Naliboki forest, creating a sustaining community of care and concern in the darkest night of history. Tuvia Bielski, trained in the interwar Polish army, famously said that he’d rather save one elderly Jewish woman than kill ten German soldiers and their local henchmen, a guiding moral principle of the indomitable Jewish spirit cultivated in Navaredok and its environs.

Navarudhak/Navaredok is but one instance of why present-day Belarus, from Brest in the west to Vitebsk in the northeast, once constituted a centerpiece of Jewish culture in Europe, inclusive of top-drawer rabbinical academies, of first-rank literature and journalism, of linguistic hothouses in which the development of both Hebrew and Yiddish could flower, and so much more. An understanding of modern Jewish life is inseparable from Belarus. The Together Plan, in making this recognition and rediscovery an essential part of twenty-first century discourse, helps to reclaim a region otherwise lost in the dark cartography of blood and mass trauma.